Bette Davis eyelids

Monday | June 4, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Bette Davis, ca. 1950; caricaturist unknown. From Miguel Andrade’s site.

DB here:

Janet Frobisher, mystery writer, has murdered her husband. Naturally, she telephones her lover and asks him to come over. But before he arrives, Janet finds that the runaway George Bates has come calling. George has been her husband’s partner in bank fraud, and now they’ve gone further. They robbed the bank at gunpoint, and a policeman was shot. George faces Janet and demands to know where her husband is.

Nobody is likely to call Another Man’s Poison (1952) a masterpiece, or an undiscovered auteur gem. (Irving Rapper has, however, signed some better-than-average pictures.) Like many ordinary movies, though, it can tell us some interesting things about cinema if we look closely. Especially when that look takes in Bette Davis.

I had to restrain myself from adding a soundtrack link for this entry. You know the one. The earworm may be at work already. But having you listen while you read would probably only distract from my point.

Eyeball to eyeball

That point is one I’ve made before. We humans are very good at watching each others’ eyes. Evolutionary psychologists debate how that skill might have evolved, but there’s little doubt that we can “mind-read” on the basis of others’ gaze direction and other eye-related cues. Of all the arts, cinema probably has the most powerful ability to galvanize and channel our reactions solely through the way people use their eyes.

But what’s an eye? I argued in an earlier entry on The Social Network that eyeballs as such aren’t very expressive, despite poets’ claims to see the soul there. Dilations are about all you get. The real expressive work gets done by gaze direction, the brows, and the lids. Blinks help too. Lately, watching films from the 1940s and early 1950s for a book I’m planning, I was struck by how the great divas of that era used their eyes.

Consider for example Barbara Stanwyck in the Mitchell Leisen weeper No Man of Her Own (1951). Helen Ferguson has innocently assumed the identity of the dead daughter-in-law of a wealthy family, and she’s torn between revealing her lie and protecting her baby. So in most scenes her look is intent and direct. She uses the screen actor’s usual tactics of steady gaze and motivated blinks, with brows and mouth carrying the emotional impact (below, shocked anxiety; then distress).

Even when she’s thinking, her eyeline remains steady and she doesn’t play much with her eyelids.

What about when Stanwyck is much less innocent, as in Double Indemnity (1944)? Devious as she is, Phyllis Dietrichson meets Walter Neff’s eyes squarely. “There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff.”

When Phillis isn’t looking straight at Neff, it’s when she’s pretending to be demure and concerned about her husband’s safety—and acting as coy as Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon. But once Neff sees through her effort to insure her husband, she glares at him unwaveringly.

Part of Stanwyck’s star persona is the bold woman who responds frankly to whatever is put before her. When it comes to evasive maneuvers, though, there’s Bette.

Putting a lid on it

Publicity photo for Jezebel.

Her eyes are big and can be quite round, of course. They also sit remarkably centrally on her face, thanks to her high forehead; this quality is accentuated when her hair is brushed back, as it often is. What especially interests me today, though, is her eyelids. If Bette rolls her eyes at us in those Warners publicity shots, she can also create hooded eyes that suggest she’s harboring secrets.

Bette has remarkable control of those eyelids; she can close them to a very exact degree. In performance, the slight drooping of the upper lid, combined with a small shift in her gaze and a turn of her head, can shade the line or word she speaks. Add that sullen mouth and her vocal tone and rhythm, and you get a nuanced suite of micro-emotions.

Take the moment in Another Man’s Poison after Janet Frobisher tells George that she’s killed her husband. She rushes into a two shot favoring her as George says: “You could’ve divorced him.” Her reaction is an eye-flick, evading his look but still radiating defiance.

Now begins a series of micro-movements that shift Janet’s reaction away from George. She explains how her husband kept her tied to him. “He/ was/clever”: On each word, her expression, eyelines, and eyelids change minutely. Then she pauses.

“He saw/ to that/ too” gets mapped onto three more changes, with traces of a smirk accompanying an eye-shift on the word “too.”

But Janet isn’t looking straight at George yet. She’s got more to say by way of explaining why divorce wouldn’t work: She and her husband continued to have sex. She puts it more indirectly: “He paid me”—pause when she lifts her eyes to look back at George—“visits.”

This instant of looking sharply back at George, as she had at the start of the shot, drives the point home and becomes the climax of this phase of the exchange. Eyelids, brows, chin, mouth, and gaze have all cooperated in creating an emotional detour away from and back to her questioner. Bette’s tiny side-glances show us a woman thinking and reacting to what she’s thinking, relishing what she’s going to say and then watching the effect of what she says. It all takes eight seconds.

Don’t be the wide-eyed ingenue

You can see the two stars’ technique operating very early in their careers. Stanwyck is the name star of So Big! (1932) and Davis is fifth-billed. Above, we find Stanwyck, playing the nobly suffering mother Selina, using her direct-gaze strategy (though as she ages, the eyes get a little pinched). By contrast, we have Davis as the saucy young illustrator Dallas O’Mara. Selina’s son Dirk asks Dallas why she doesn’t love him. When she answers, William Wellman’s staging gives Davis a little aria of face-time at the piano.

Dallas explains that she’s attracted to men who have confronted the rough side of life. I can provide only excerpts of what is a forty-second shot, full of shifts of head position, facial expressions, and eye movements, complete with finely calibrated eyelid work. The passage reminds us that Davis’ dynamic expressions and eye movements are often motivated by her playing characters full of jittery pep, talking fast and thinking faster. She will even deliver phrases with her eyes closed—here, speaking of men with hands scarred from work and struggle.

As she says, “You haven’t a mark on you, Dirk,” Dallas reaches across to grip his forearm. A new phase of the scene begins, but still with the suite of slight head turns and eyelid action.

Dallas says that if he’d kept on as an architect instead of taking refuge in a safe business job, his face would show it. As in Another Man’s Poison, Davis concludes her monologue by turning to face the man and deliver the final line directly. From early in the scene, however, Dirk has turned his face aside in shame.

Where would his marks of character show? “In your eyes, in your whole being.” She peers up at him, her face closer than at any other point in the scene, and her hand lifts from his arm to accentuate her frank but brutal blow to his pride.

Which makes our last view of her all the more arresting. In the final scene, Dallas meets Dirk’s mother and imagines her as an ideal subject for a portrait. Now the flighty young artist is riveted on the steady, serene gaze of the older woman.

In this climax, Dallas becomes what Dirk has called her—“a wide-eyed ingenue”—but in her rapt admiration she proves herself worthy to be Selina’s daughter-in-law.

Bette, eyeballing us

Now that we know the role Bette’s upper eyelids play, we can appreciate other moments when she milks their effects virtuosically. Go back to Another Man’s Poison. George tells Janet that he has the weapon used in the bank robbery—the pistol that bears her husband’s fingerprints. As George starts his line, she’s taking a drink in the foreground. Lifting the glass, she tips her head back too so that her eyes are just visible under her lids—and they’re looking out at us.

George says, “I’ve got the gun.” Janet lowers the glass, but she keeps it poised. Now her lids and eyelines present her reaction to George’s information that the pistol bears the husband’s fingerprints. You see her thinking about evasive action.

This moment in effect spotlights Davis’ use of her eyes; she’s frozen in place, and they’re the only things that move.

Early in the film, we’re given a sort of primer that trains us to watch Janet/ Bette’s eyelids. The first scene shows Janet making her call to her lover from a phone booth. It’s staged with her in profile, so that her brows and mouth are relatively unmoving and the eyelids, centered in the frame, become quite salient. I won’t try to follow all their tiny fluctuations, in coordination with the chin’s angle and the mouth, but these samples should give you the flavor. (Note the very slight difference between the first and the third image, and the second and the fourth).

A more frontal view of La Davis would have been a more characteristic star introduction, but it’s as if the film is saving her full-face firepower for later scenes.

There’s other evidence that Bette was considered to be able to hold a scene by an eyelash. In Payment on Demand (1951), flashbacks from Joyce and David’s miserable marriage take us to happier days. One scene shows the couple embracing on a hospital bed after Joyce has given birth to their second child.

Joyce learns of David’s plans to move out of town, but she resists and sits upright. This brings her distraught reaction home to us with the now familiar coordination of eyeline, eyebrows, and eyelids with the mouth and shakes of the head—another suite of micro-behaviors I can merely sample here.

But then Joyce relaxes and falls back, hiding her face as the camera cranes up slightly.

Director Curtis Bernhardt has reframed the shot so that as Joyce curls up on the pillow, one eye peeps out. We don’t see her mouth replying to David’s lines, but we get the customary fractional eyelid changes, as in the phone booth scene above.

Eventually Davis moves her shoulder and reveals Joyce’s mouth, but for several seconds we’ve been obliged to follow the small movements of her lids as the only clue to her calming down—and getting her way with David. This is, needless to say, all done without a close-up.

Hollywood cinema is a highly formal cinema, as conventional in some ways as commedia dell’arte. Yet that doesn’t mean it must trade only in gross effects. Admittedly, much of today’s cinema has sacrificed nuance for brute force. All the better, then, that returning to even minor films from the studio era can remind us of how many opportunities the medium affords.

Bette Davis isn’t the only virtuoso performer, of course, and many of her contemporaries show the same kind of gifts, sometimes put to different ends. She offers a convenient illustration of how film actors can cultivate meticulous control over facial regions we don’t normally think about. She makes up for being short and rather slight by playing her face like a chamber ensemble, with every “voice,” eyelids included, contributing to the restless dramatic flow.

Okay, I know: The song was running through your head all the way through. You deserve a break. Go ahead, but you might as well watch something too.

On the evolutionary implications of our eye behavior, see Michael Tomasello et al., Why We Cooperate (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009). Tomasello argues that the need for social cooperation favored signals of shared attention; to work together, we need to notice things that other people are looking at. He also points out:

All 200-plus species of nonhuman primates have basically dark eyes, with the sclera—commonly called the “white of the eye”—barely visible. The sclera of humans (i.e., the visible part) is about thee times larger, making the direction of human gaze much more easily detectable by others. A recent experiment showed that in following the gaze direction of others, chimpanzees rely almost exclusively on head direction—they follow an experimenter’s head direction up even if the experimenter’s eyes are closed—whereas human infants rely mainly on eye direction—they follow an experimenter’s eyes, even if the head stays stationary (pp. 75-76).

But tracking my eye direction helps you, not me; how could it have evolved? Tomasello hypothesizes that making eye direction salient developed in a cooperative social environment. It’s part of social intelligence, in which mind-reading works to everyone’s benefit in shared tasks.

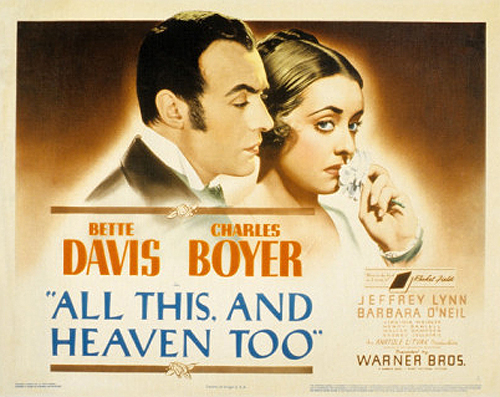

A vast resource on all things Bette is this site. Some perceptive remarks on her acting style are at Uncle Eddie’s Theory Corner. Jim Emerson offers an interview with Miss Davis in a smoke-filled room, while Roger Ebert presents an admiring appreciation of All About Eve.

An earlier blog entry here reflects on the performance of another sacred diva of the period, Joan Crawford. If you’re interested in a wider account that fits such matters into a broader theoretical perspective, including folk psychology, try this essay.